Background

What does it mean when the very foundations of industrial advancement become the greatest danger to human survival on the planet? What does a just future look like for communities built on coal? How do we reconcile the pace of climate aspirations with the ground-level realities of coal-producing communities? Can a coal economy truly shift without traumatic social disruption? Who decides what a “just transition” looks like—and for whom? These are not theoretical questions at all—they are place-based challenges that need real solutions and were the focus of the conversation during the 2025 Global Coal Transition Workshop that took place at the University of Queensland in Australia in May 2025.

Coal—a long-standing proxy for energy independence and economic prosperity—now finds itself at the center of one of the most current and urgent global dilemmas: how to turn off a carbon-based legacy without abandoning individuals and economies along the way. Despite decades of climatic debates, coal remains entrenched within the global energy system. Up to 2023, it accounted for approximately 26% of primary energy use and 37% of global electricity generation, qualifying it as a giant in powering the world (Liu et al., 2024). And it is this dominance that renders coal the most carbon-intensive of all the fossil fuels, releasing over 15 billion tons of CO₂ each year—more than any other energy source (Wang et al., 2024). The IPCC warnings are clear: if global warming is to be kept to 1.5°C, then coal consumption must fall by 75% by 2030 and by as much as 97% by 2050.

Complicating this challenge is the issue that the global coal reserves are highly concentrated, with just five countries—the United States (22%), Russia (15%), Australia (14%), China (14%), and India (11%)—holding about 75% of total reserves (Raza et al., 2024). While 84 countries have pledged to phase out the development of new unabated coal power stations, big emitters like China and India, which together produce nearly two-thirds of coal power, are adding capacity to meet growing demand. This situation leads to a very uneven global shift, filled with both progress and contradictions, highlighting the urgent need for tailored and fair transition plans that consider climate needs alongside energy security and people’s jobs.

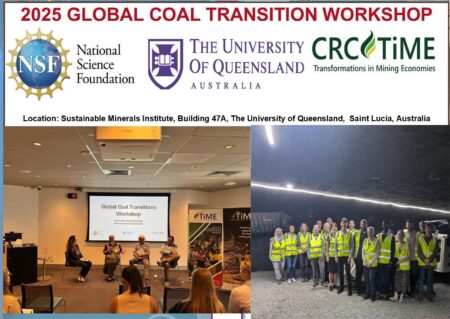

This balance—between energy realities and climate demands—is not simply aspirational goal-making. It requires practical, fair, and inclusive transitions that are as much about places and people as they are about megawatts and emissions. It is against this complicated and pressing backdrop that the 2025 Global Coal Transition Workshop was organized at the University of Queensland, Australia. The workshop was part of the U.S. National Science Foundation (NSF)-funded research project on Global Coal Transitions, with Prof. Max Woodworth (Principal Investigator) and Prof. Jeffrey Jacquet (Co-Principal Investigator). Supported by the Cooperative Research Centre for Transformations in Mining Economies (CRC TiME), the workshop convened researchers, policymakers, and frontline practitioners to share knowledge and discuss evidence-based responses to the social, environmental, and economic aspects of coal phased out in varied international contexts.

From Columbus to Queensland: My journey to the 2025 Global Coal Transition Workshop

As a doctoral student, I was overjoyed when my advisor, Professor Max Woodworth, first informed me in November 2024 of his plans to facilitate my participation in the 2025 Global Coal Transition Workshop in Brisbane, Australia, under his research grant from the US National Science Foundation. This was a few months after I had moved to the U.S. to pursue my PhD in Geography at The Ohio State University. As an aspiring resource and environmental geographer, I saw it as a special opportunity for personal and professional development. To me, it was not just a chance to travel abroad to attend my inaugural international conference but also a lifetime opportunity to learn from and engage with leading scholars, industry practitioners, and policymakers who are at the forefront of the coal transition debates on one of the most significant environmental and socio-economic concerns of our era: the sustainable and equitable phase-out of coal. Driven by learning and purpose, I began the visa process in February 2025 and prepared myself for what I knew would be a learning experience that would transform me. Fast forward to May 9, 2025: Professor Max Woodworth, my advisor, and I boarded a flight from Columbus, USA, and arrived in Brisbane, Australia, on May 11, 2025. To me, this transformative journey was more than physical—it was a move in a career commitment to understanding interconnected environmental justice, energy geography, and sustainable development challenges.

Voices in Transition: Highlights from the 2025 Global Coal Transition Workshop

The 2025 Global Coal Transition Workshop was held at the Sustainable Minerals Institute (Building 47A) in the beautiful grounds of the University of Queensland in St. Lucia, Australia. Professor Tom Measham and Dr. Ami Fadhillah Amir Abdul Nasi at the Sustainable Mineral Institute ensured that everyone had a positive and fulfilling time through their thorough organization, coordination, and hospitality.

The Steering Committee of the Research Coordination Network (RCN) convened a meeting on Monday, May 12, 2025, at Building 47A to brainstorm on many issues relating to ongoing research, future collaborations, and strategies for information dissemination on the global coal transition beyond the confines of the workshop.

Fig. 1: Panel Discussion on First Nations perspectives on coal transitions

The workshop on Tuesday, May 13, 2025, began with a panel discussion on First Nations perspectives on coal transitions featuring academicians and Aboriginal representatives from First Nations communities. Their speaking added a passionate kick-off with the voices resonating strong on Indigenous sovereignty, remembering the people, and the ethical imperative of true participation. This was followed by a series of sessions on the governance of transition, justice and fairness, and the stakeholder process of collaboration. The day concluded with a compelling discourse on the ways in which method, politics, and narrative influence the practice and perception of coal phase-outs, emphasizing the necessity of inclusive, place-based approaches that consider power dynamics and lived experience in transition planning.

The workshop on Wednesday, May 14, 2025, started with deeply reflective discussions about post-mining legacies and future imaginaries. Presenters shared research that was both analytical and moving, laying bare how individuals in post-coal towns in the United States, Europe, and Australia are grappling to fill gaps—physical, emotional, and economic. The final panel, “Regional communities, dialogue, and the role of government,” picked up on the tension and potential of state-led versus grassroots processes. The crowd of attendees debated accountability, transparency, and adaptive governance questions.

Fig. 2: Session presentation and engagement

While the workshop was full of lessons, something that hit—and continues to echo in my mind as an emerging scholar deeply interested in resource and environmental justice in mineral-rich communities—is the need to place community agency at the center of transition planning. Research, particularly in the Global South shows that far too often, the future of mineral-rich communities is decided without the most affected being at the table. The workshop underscored that fair transitions should prioritize environmental ambitions while enabling local voices, particularly historically excluded ones, to be empowered in determining the directions ahead. The complex stories, the nuanced ethical implications, and the cross-region contrast issues discussed at the workshop challenged me to think more profoundly about what exactly justice in the worlds of extractive environments might look like.

Seeing is Understanding: A Field Immersion into Bowen Basin’s Coal Mining Landscape and other areas

As part of the 2025 Global Coal Transition Workshop, participants experienced the rare opportunity to move beyond theory and debate to situated, grounded observation. On Thursday, we journeyed into the Bowen Basin—one of Australia’s most prolific coal mining regions—for an all-day field immersion with Stanmore, one of the region’s key industry players. The tour was an eye-opening experience of the realities and nuances of mining and post-mining in Central Queensland.

Upon arrival, we were greeted by the Stanmore team, and the ease and transparency of their approach immediately established a tone for productive exchange. The visit started with a presentation that provided an overview of the company’s operations at present, safety policies, environmental policies, and future. We put on our safety gear and toured some open-cast mining sites, witnessing up close the size and intricacy of coal production. A walk-through the processing center provided a glimpse into how raw coal is graded and prepared for both domestic and export markets. For most of us in the academia and policy background, it offered a real-world understanding of the often-abstract concept of the coal value chain. From the open-cast mining sites, we proceeded to the rehabilitation sites, where mined-out land is being reshaped and replanted to restore ecological balance and aesthetic integrity. The Stanmore team took us through their reclamation process, which involved backfilling and landform reconstruction to control erosion and stability, topsoil restoration and revegetation, and programs to monitor the ecosystem’s health over time. Stanmore’s rehabilitation project exemplifies not only its technical execution but also its serious approach to ecological restoration, which is a top priority rather than an afterthought. Their example provides lessons for mining operations worldwide: rehabilitation is not just a compliance issue—it’s an issue of legacy, accountability, and re-establishing the social license to operate. This experience served to underscore the importance of having effective, enforceable post-closure plans integrated into the Environmental and Social Impact Assessment (ESIA) process of all mining projects. Practically, rehabilitation cannot be voluntary or last-minute in mining—it needs to be planned from the beginning, well budgeted for, and carried out in a transparent manner. At a time when environmental justice and public trust are more crucial than ever, the land’s long-term health following mining should serve as the ultimate indicator of a mine’s success. The field visit serves as a testament to the importance of sight and insight. Policy documents and scholarly frameworks can only provide a limited understanding compared to the firsthand experience of walking the ground, inhaling dust, and observing the work (and limitations) of remediation efforts.

Fig. 3: Participants at the Stanmore Mine Site

Fig. 3: Stanmore’s Post-Mine Rehabilitation Project

Friday’s tour was the last part of our field experience in the Central Queensland. Like the earlier visit to the Bowen Basin, it provided a captivating blend of innovation and sustainability. We left Moranbah in the morning and traveled to Mackay, where we were welcomed at the Resources Centre of Excellence (RCoE). The CEO at RCoE gave us a powerful presentation about the center’s vision of driving innovation and the best practices within the resources sector. The talk was followed by a guided walk through the RCoE facility—a state-of-the-art research, training, and industry collaboration hub. One standout feature at the RCoE was the underground mine simulator, which provided a very realistic, experiential understanding of how underground mining activities are conducted. The underground simulator provided a fantastic insight into the physical conditions under which miners work, the safety protocols employed, and other complex mining activities that define real-world underground mining activities. We followed the visit with a leisurely lunch at the RCoE premises

Fig. 4: A post-workshop visit to the underground mine simulation facility at the Resource Center of Excellence.

During the afternoon, the group toured the Mackay Renewable Biocommodities Pilot Plant, located in the city center. Here, we learned about the groundbreaking efforts underway to transform agricultural waste and biomass into renewable materials and fuels. The tour of the facility was both technical and inspiring, illustrating the region’s progressive attitude toward renewable energy and circular economies. We concluded the day by taking a flight back to Brisbane, armed with fresh knowledge on how resource-based communities are testing and adapting to a sustainable future.

Conclusion

Attending the 2025 Global Coal Transition Workshop and Field Trip was a deeply transformative experience—professional, intellectual, and personal. The Bowen Basin and Mackay field trips showed the value of experiential learning. Walking through operating mines and observing the open-cast mining and post-mine land rehabilitation processes at Stanmore’s site, as well as experiencing an underground mining scenario at the Resource Centre of Excellence, provided concrete meaning to many concepts I had previously only learned about in theory. These field visits reminded me of the importance of my fieldwork in Ghana—not simply as a data-collection exercise, but as a discipline of immersion in the everyday realities of mining-affected communities. Thank you to Prof. Max Woodworth and Prof. Jeffrey Jacquet for facilitating this, and to all the participants whose willingness to share generously, think critically, and collaborate made the 2025 Coal Transition Workshop not just informative but positively influential in shaping how we imagine—and provide—just futures in extractive regions.

Max Woodworth

Jeffrey Jecquet

Tom Measham

References

Raza, M. A., Karim, A., Aman, M., Al-Khasawneh, M. A., & Faheem, M. (2024). Global progress towards the Coal: Tracking coal Reserves, coal Prices, electricity from Coal, carbon emissions and coal Phase-Out. Gondwana Research. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gr.2024.11.007

Liu, T., Zhao, G., Qu, B., & Gong, C. (2024). Characterization of a fly ash-based hybrid well cement under different temperature curing conditions for natural gas hydrate drilling. Construction and Building Materials, 445, 137874. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2024.137874

Wang, Y., Quan, S., Tang, X., Hosono, T., Hao, Y., Tian, J., & Pang, Z. (2024). Organic and inorganic carbon sinks reduce Long‐Term deep carbon emissions in the continental collision margin of the southern Tibetan Plateau: Implications for Cenozoic climate cooling. Journal of Geophysical Research Solid Earth, 129(4). https://doi.org/10.1029/2024jb028802